Published online Dec 22, 2015. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i4.352

Peer-review started: May 28, 2015

First decision: June 18, 2015

Revised: July 7, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: December 22, 2015

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia including social withdrawal, diminished affective response, lack of interest, poor social drive, and decreased sense of purpose or goal directed activity predict poor functional outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. They may develop and be maintained as a result of structural and functional brain abnormalities, particularly associated with dopamine reward pathways and by environmental and psychosocial factors such as self-defeating cognitions and the relief from overstimulation that accompanies withdrawal from social and role functioning. Negative symptoms are more difficult to treat than the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and represent an unmet therapeutic need for large numbers of patients with schizophrenia. While antipsychotic medications to treat the symptoms of schizophrenia have been around for decades, they have done little to address the significant functional impairments in the disorder that are associated with negative symptoms. Negative symptoms and the resulting loss in productivity are responsible for much of the world-wide personal and economic burden of schizophrenia. Pharmacologic treatments may be somewhat successful in treating secondary causes of negative symptoms, such as antipsychotic side effects and depression. However, in the United States there are no currently approved treatments for severe and persistent negative symptoms (PNS) that are not responsive to treatments for secondary causes. Pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatments are currently being developed and tested with severe and PNS as their primary targets. Academia, clinicians, the pharmaceutical industry, research funders, payers and regulators will need to work together to pursue novel treatments to address this major public health issue.

Core tip: Negative symptoms of schizophrenia including social withdrawal, diminished affective response, lack of interest, poor social drive, and decreased sense of purpose or goal directed activity predict poor functional outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. Negative symptoms and the resulting loss in productivity are responsible for much of the world-wide personal and economic burden of schizophrenia. We describe current theories of negative symptom development and maintenance and address the data regarding current and emerging treatments. Negative symptoms represent an unmet therapeutic need for large numbers of patients. Academia, clinicians, the pharmaceutical industry, research funders, payers and regulators will need to work together to pursue novel treatments to address this public health issue.

- Citation: Sarkar S, Hillner K, Velligan DI. Conceptualization and treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatr 2015; 5(4): 352-361

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v5/i4/352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i4.352

Schizophrenia is one of the top 10 disabling mental conditions and impacts 1% of the adult population worldwide[1]. Patients suffering from schizophrenia struggle with cognitive and functional impairment. Due to the often chronic course of illness, patients with schizophrenia have poor educational attainment, reduced quality of life, impairment in independent living and major socio-occupational dysfunction[2,3]. Impairment arising from schizophrenia is so severe that only 10%-20% of patients work full time or part time[4]. The majority of patients suffering from schizophrenia require some form of public funding for support. The loss of productivity associated with schizophrenia is a major driver of cost which is estimated to be over 60 billion dollars annually; or more than $1000 for every man, woman, and child in the United States[5-9]. There is an additional burden on the family members and relatives who care for such patients[10].

Much of the burden of schizophrenia is due to what are called the negative symptoms. This manuscript will review the definition of negative symptoms, describe the onset and maintenance of these symptoms and identify potential treatments.

Negative symptoms are defined as absence or reduction of behaviors that are normally present in the general population[11]. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia include social withdrawal, diminished affective response, lack of interest, poor social drive, and decreased sense of purpose or goal directed activity[11]. DSM-V emphasizes two negative symptom domains: expressive deficits and avolition[12]. Expressive deficits include blunted facial expression, few changes in voice tone, and a paucity of expressive gestures which are normally present in conversation. Avolition refers to a lack of initiative for daily activity and interaction with others. Individuals with avolition may have difficulty even generating an idea to do something, and have low levels of productive activity during the day[13]. They may spend a lot of time sitting or lying around, have few interests and relate little to others[12-15].

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia persist longer than positive symptoms and are more difficult to treat[16,17]. In addition, negative symptoms of schizophrenia serve as better predictors of concurrent and future socio-occupational functioning than do positive symptoms[18-20]. A large number of studies have found attenuated negative symptoms in patients with at risk mental states[21]. In fact, the severity of negative symptoms rather than positive symptoms has been found to predict conversion to psychosis in patients with at risk mental states[22]. Persistent negative symptoms (PNS) are present in about one third to one-half of first episode psychosis (FEP) patients[23,24].

Moreover, those FEP patients who demonstrate negative symptoms at baseline show significantly worse functioning when assessed again at 12 mo in comparison to FEP patients without negative symptoms[23]. Therefore, decreasing negative symptoms and improving functional outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia is an important public health issue. Effectively treating negative symptoms could help to prevent long term disability in first episode patients with schizophrenia.

Approximately 20%-40% of patients with schizophrenia have persistent or deficit negative symptoms[25]. Primary (deficit) negative symptoms are defined as symptoms that are idiopathic to schizophrenia, arising from a distinct yet ultimately mysterious underlying pathologic process. These symptoms are present during and between episodes of symptom exacerbation and are not always dependent on whether the patient is taking medication[11,26,27].

Secondary (non-deficit) symptoms are defined as those that are caused by factors other than the illness of schizophrenia[11]. Secondary causes of negative symptoms can include medication side effects, notably extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) of antipsychotic medication, neuroleptic akinesia, or drug withdrawal from Central Nervous System stimulants[11,15]. Secondary negative symptoms can also be due to depression, social deprivation or personality disorders[11]. Secondary negative symptoms may be non-persistent or appear for a shorter duration when compared to primary negative symptoms[16].

Data suggest that individuals with deficit syndrome have poor premorbid functioning prior to their first episode of psychosis than individuals without deficit syndrome, and are less likely to be married[28-35]. In addition, some studies report more severe cognitive impairments, and distinct neuroimaging findings in deficit syndrome[34-38]. The differences between deficit and non-deficit forms of negative symptoms may suggest that deficit syndrome represents a separate disease entity. However, it has also been argued that the deficit syndrome lies on a continuum of severity within schizophrenia and does not characterize a distinctly separate subgroup[39]. In practice, it can be difficult to distinguish the primary vs secondary negative symptoms of schizophrenia and they may coexist.

The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms suggests that treatment development should focus on PNS[40]. PNS are defined as either primary or secondary negative symptoms that are present for a minimum of 6 mo duration, and are not responsive to any potential treatments for secondary negative symptoms[11]. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms indicated that PNS represent an unmet therapeutic need for patients suffering from schizophrenia[40,41].

Alterations in neurotransmitter systems which could be either neurodevelopmental in origin or develop secondary to dopaminergic blocking medications may predispose a person to develop negative symptoms of schizophrenia[42,43]. Prior studies have indicated that disruptions in ventral striatal reward systems are associated with the development of negative symptoms[44,45]. Some studies have highlighted dopaminergic and noradrenergic circuitry involved with reward as neural substrates for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia[46,47]. Alterations in normal connectivity among brain regions have been implicated. Even individuals at high risk for psychosis have demonstrated alterations in functional brain connectivity. Dandash et al[48] have demonstrated that conversion to psychosis from an at risk mental state is mediated by alterations in both dorsal and ventral corticostriatal systems. Moreover, studies of brain structure have shown negative symptoms to be associated with subtle tissue decrements in the frontal lobes[38,49-56]. A correlation has also been found between severity of negative symptoms specifically and the right posterior superior temporal gyrus, with the greater severity of negative symptoms being correlated with larger volumes of gray matter in this region[57]. While many of these abnormalities are clearly present prior to the development of a full blown psychotic disorder, it is difficult to say whether these structural and functional changes are causally related to the development of negative symptoms in particular[58].

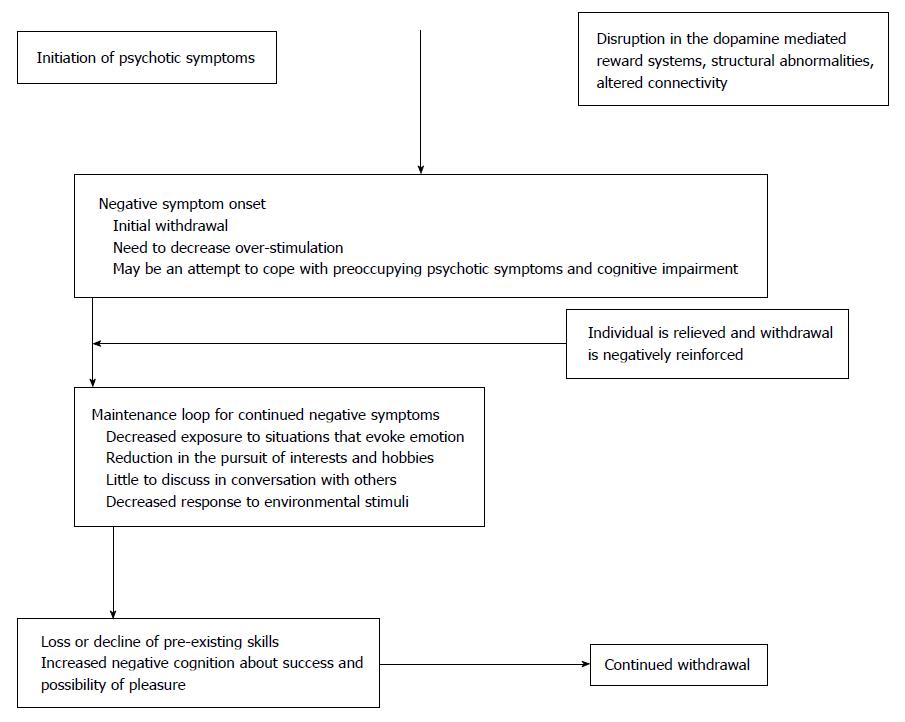

In addition to brain structure and functioning, negative symptoms may also develop during early stages of psychosis as a psychosocial defense mechanism for dealing with distress beyond one’s capacity to cope[59]. In this model, exposure to overwhelming social and environmental stimuli leads to shutting down of various psychological systems, presenting as negative symptoms. This removal of distressing stimuli by shutting down is negatively reinforcing as the person experiences relief. This contributes to a dependence on negative symptoms like social isolation, apathy, and avolition to reduce exposure to and the impact of aversive or over stimulating experiences[59]. Thus, the mechanisms involved in the development of negative symptoms are multifactorial and may include structural, neurobiological, environmental and psychosocial factors.

Velligan et al[60] proposed a negative symptom maintenance loop. According to their model, dysfunctional brain reward systems and/or the onset of psychotic symptoms and associated psychosocial withdrawal leads to a maintenance loop wherein decreased initiation and withdrawal lead to a series of self-perpetuating outcomes including decreased responsiveness to environmental stimuli, a lower level of interest in the world, little to discuss in conversations with others, a low level of reinforcement from the person’s surroundings, lower levels of overall stimulation, loss of skills previously attained for work or socializing with others, and decreased planning for the future such that everyday looks very much the same.

Moreover, when someone with negative symptoms is asked to participate with others or attempt something new, self-defeating cognitions about failure or ridicule may prevent the person from trying activities[59,61]. Repeated negative consequences and failures following the initiation of various tasks and behaviors may further prevent initiation of activities[59]. This negative feedback loop persists and makes it difficult to break the cycle leading to maintenance of negative symptoms[61,62].

Additionally, a study conducted by Gard et al[63] indicated that individuals with schizophrenia are less able than others to anticipate enjoyment (anticipatory pleasure) in spite of experiencing enjoyment to a similar extent (consummatory pleasure) when engaging in activities. This reduced ability to anticipate pleasure may lead the individual to perceive that the effort required to engage in behaviors, interact with people or pursue interests will not be worth the benefits achieved. This situation ultimately leads to reduced planning of activities that actually may be pleasurable[60].

The onset and maintenance of negative symptoms is described in the figure below adapted from Velligan et al[60].

Patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia are frequently brought in for an assessment by their close relatives as part of family conflict with the chief complaint of poor social functioning[64,65]. Instruments developed to measure the negative symptoms are primarily used for research purposes[66-69]. Rating scales used to measure the negative symptoms of schizophrenia include the Negative Symptom Assessment (NSA-16)[66], Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale[68], Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms[70], the Brief Negative Symptom Scale[69] and the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS)[67]. The majority of these scales provide definitions of each negative symptom domain, a semi-structured interview to obtain needed information and a series of behavioral anchor points to help the rater identify the frequency, severity and intensity of each symptom type. A brief description of these scales, item scoring, and domains assessed appear in Table 1. Studies have demonstrated very high correlations among negative symptom measures averaging around 80, which suggesting that they are all tapping the same construct[66,67,69,71]. These instruments form the basis for determining the presence of PNS according to the NIMH-MATRICS consensus guidelines[40]. Guidelines require that a patient must have at least moderate scores on at least two negative symptom domains which persist for a minimum of 6 mo, along with low levels of positive symptoms, depression and EPS[40].

| Assessment name | Scale | Negative symptom domains measured |

| Negative Symptom Assessment (NSA-16) | Score of 1 (normal)-6 (severe) | Five domains (each domain has several specific symptoms listed): Communication, Emotion/Affect, Social Involvement, Motivation, Retardation |

| Each symptom within the 5 domains is scored separately | ||

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | Score of 1-7 on each item. Score of 7 indicates higher symptom severity | Seven domains: Blunted Affect, Emotional Withdrawal, Poor Rapport, Passive/apathetic Social Withdrawal, Difficulty in Abstract Thinking, Lack of spontaneity and Flow of Conversation, Stereotyped Thinking |

| Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms | Score of 0 (absent) -5 (severe) Each symptom within the 5 domains is scored separately | Five domains (each domain has several specific symptoms listed): Affective Flattening or Blunting, Alogia, Avolition-Apathy, Anhedonia-Asociality, Attention |

| Brief Negative Symptom Scale | Score of 0 (absent) - 6 (severe) | Six Domains (each domain has several symptoms listed): Anhedonia, Distress, Asociality, Avolition, Blunted Affect, Alogia |

| Each domain is scored | ||

| Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms | Score 0 (no impairment) -4 (severe) | Five Domains (each domain has several specific symptoms listed): Asociality, Avolition, Anhedonia, Affective Flattening, Alogia |

| Each symptom within the 5 domains is scored separately | ||

| Brief Negative Symptom Assessment | Score 1 (normal)-6 (severe) | Four Domains: Prolonged Time to Respond, Emotion, Reduced Social Drive, Grooming and Hygiene |

| Four item Brief Negative Symptom Assessment | Score 1 (normal)-6 (severe) | Four Domains: Restricted Speech Quantity, Reduced Emotion, Reduced Social Drive, Reduced Interests |

Unfortunately, the scales listed above are too lengthy for use in typical community mental health centers treating large numbers of patients. In fact, for clinicians, negative symptoms are often not a focus of assessment or treatment because they are rarely a reason for patients to be in crisis or pose a need to go to the hospital. However, assessing negative symptoms will become increasingly important as medications are developed specifically to target these symptoms. In clinical interviews, it is important to assess daily activities, social relationships within and outside of the family, and work or school involvement and performance. Several brief 4-item measures of negative symptoms for use in clinical situations are available[66,72]. Some items on each scale require no questioning as they are based upon observation of the patient. Such scales have been used reliably in busy community mental health departments seeking to promote outcomes-based treatment[72].

Treatment of negative symptoms depends upon their causes. If negative symptoms such as social withdrawal are secondary to a patient’s positive symptoms then increasing the dosage of antipsychotic medication or switching to a different antipsychotic medication may be helpful[73]. Alternatively, if negative symptoms are associated with depressed affect, then treatment for depression should be considered[74]. A recent Cochrane review of the literature indicated that antidepressants may have a positive impact on negative symptoms, however additional prospective studies are needed on a larger-scale to reach this definitive conclusion[75]. Moreover, it is not clear from the existing literature whether antidepressants improve negative symptoms in the long term, as most randomized blinded trials have been brief. If the occurrence of negative symptoms are secondary to EPS of antipsychotic medications, these can be potentially decreased by reducing the dosage of antipsychotic medication to a level that does not produce EPS or by prescribing atypical antipsychotics with lower potential for EPS side effects[76]. Of course problems with increasing positive symptoms may result from lowering the dose of antipsychotic medications.

Currently there are no approved treatment options for PNS that are not responsive to treatments for secondary causes in the United States. Some evidence for efficacy of second generation antipsychotics has been reported, and Amisulpride (not available in the United States) is approved for treatment of negative symptoms in Europe and Asia[77-79]. However, none of the studies mentioned above included design features established by expert consensus as necessary to prove efficacy for PNS[11]. The design features deemed necessary include documentation for persistence of negative symptoms for a minimum duration of 6 mo, relatively low and stable positive symptoms, low levels of depression, and stable medication side effects. Such studies cannot rule out pseudospecificity in which negative symptoms improve secondary to improvement in positive symptoms, depression or EPS[11].

According to the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) U.S. schizophrenia guidelines, no pharmacologic treatment for negative symptoms has proven to have sufficient evidence to support a recommendation, indicating a significant unmet need for important treatment in this area[80].

Novel compounds exerting action on the glutamate system have demonstrated some initial efficacy in negative symptoms. For example, a phase II randomized controlled trial with bitopertin (RG1678), a glycine transporter inhibitor when added to standard antipsychotic therapy for 8 wk demonstrated statistically significant improvement on negative symptoms when compared to antipsychotic treatment plus a placebo[81]. In this trial, a positive trend for functional outcome was also observed in the Bitopertin group. Unfortunately, these results were not replicated in larger scale trials. Phase III trials of Bitopertin did not support its efficacy for the treatment of negative symptoms[82]. There is limited evidence supporting alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor co-agonists as treatments for negative symptoms[83]. In a placebo controlled, randomized double-blind study, folic acid and B12 significantly improved the negative symptoms, but the treatment response was related to genetic variation in folate absorption[84]. Clinical trials of medications for treating negative symptoms have been described in depth by Arango et al[85]. A continued effort to find viable pharmacologic options for the treatment of negative symptoms is needed.

Adjunctive psychosocial therapies (cognitive remediation, social cognition training, family intervention, social skills) have been found to be effective in the treatment of schizophrenia[86,87]. Among these psychosocial treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has demonstrated some improvement in negative symptoms of schizophrenia[88,89]. In addition, in a small study, body-oriented psychotherapy directed towards getting the individual moving around and developing self-awareness with environmental boundaries was successful in reducing the negative symptoms of schizophrenia[90]. Some studies suggest that negative symptoms may improve in cognitive remediation (CR), a treatment targeting attention, memory and planning[91-93]. However, the most successful CR studies are imbedded in larger psychosocial treatment programs, which makes the impact of CR alone unclear for negative symptoms. Social skills training targets social adaptation, improves social skills and functioning in patients with schizophrenia[94,95]. Cognitive Adaptation Training (CAT) is a home based manual-driven treatment that involves the use of environmental supports and cues (signs, alarms, checklist) to bypass the cognitive impairments characteristic of schizophrenia with the goal of improving community functioning[96,97]. In multiple studies CAT has improved targeted behaviors (medication adherence, grooming socializing) and functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia[97-100]. CAT has been found to improve one negative symptom dimension, the motivation factor of the NSA, with moderate effect sizes in published studies[101].

None of the studies mentioned above included design features established by expert consensus as necessary to prove efficacy for PNS[40]. Studies that do not include these design features may reduce only secondary causes of negative symptoms rather than addressing the primary or PNS of schizophrenia.

Motivation and Engagement Training (MOVE) is a novel home based, multi-modal, integrated psychosocial treatment developed by Velligan et al[60] to specifically address all negative symptoms domains. MOVE is designed to break the negative feedback maintenance loop described in Figure 1 and incorporates 5 components: Antecedent control, Anticipatory pleasure alteration, Emotional processing, CBT for negative cognition, and Skill building[60].

Antecedent control refers to external cues (signs, checklist) along with the placement of supplies in the home with the goal of cuing behavior and increasing the initiation of activity, establishing habits and increasing automaticity[96-99]. When behaviors are externally cued, the individual does not have to generate a plan[97-100]. Decreasing the steps required for completing each task through organization and task analysis also increases the probability that a task will be attempted and completed successfully[60].

MOVE also targets deficits in anticipatory pleasure. These deficits may prevent an individual from perceiving that he will enjoy an activity or that the activity will be worth the effort needed to pursue it[63]. In MOVE treatment, anticipated pleasure is elicited prior to participating in a pleasurable activity and again during that activity[60,63]. This information is used to teach the individual about the discrepancy between anticipated and experienced pleasure. The MOVE therapist discusses with the individual how problems in anticipatory pleasure may interfere with planning recreational and social activities. Statements about the level of enjoyment an individual actually experiences during the activity are recorded and replayed for cueing future activities. Photographs of this enjoyment may be placed on the person’s wall to remind the person of their pleasure and increase the probability of planning similar events in the future[60].

Emotional processing targets both the identification of emotion and its expression. Individuals with schizophrenia often experience difficulty identifying their own feeling states[60]. MOVE therapists use graded check-ins with errorless learning methods that enable the individual to identify or label their own emotions. Multiple techniques including voice and visual recording are used to help individuals learn to successfully convey these emotions with appropriate facial expression, voice modulation and gestures. Computer exercises based upon Social Cognition Interaction Training are utilized to improve identification of the emotions of others[102].

CBT techniques are used in MOVE to address self-defeating negative thoughts that prevent initiation of and participation in social activities[59]. Cognitive distortions (“No one will like me, I will be alone all night at the party.”) are identified and the person is helped to come up with more accurate self-assessments[59].

Skill training is a final component of MOVE. Behavioral techniques (shaping, modeling) are used to coach the individual to perform various social and independent living tasks (e.g., returning an item to a store). Trainers assist the patient with these tasks not in a group at a clinic but in vivo in relationship to situations the person needs to address in their daily lives[60].

In MOVE, positive reinforcement initially encourages behavioral attempts. Successful completion of activities is thought to improve the individual’s self-efficacy[60]. A sense of self-efficacy leads to increased willingness to try new behaviors[60]. Higher productivity provides an opportunity for the individual to share new activities in conversation with others[60]. Skills building strategies can help to increase success in social interactions and improve enjoyment[102,103].

A recent study of 50 patients randomized to MOVE vs treatment as usual (medication follow-up and case management only) found that MOVE improved negative symptoms as assessed on the CAINS and the NSA-16[71]. Effect sizes were moderate and suggest that larger studies of MOVE may be warranted.

Negative symptoms are devastating for patients and families. They contribute to the high levels of disability observed in schizophrenia. Negative symptoms are difficult to treat with currently available pharmacotherapies. While some improvements have been noted with psychosocial treatments, few have been studied with design features needed to establish their efficacy in the treatment of PNS. Brief reliable and valid assessments of negative symptoms are available but need to be made widely available to clinicians. Treatments of secondary causes of negative symptoms are important to attempt. Despite these challenges, continued work on treatment development involving a concentrated effort from academia, clinicians, the pharmaceutical industry, payers, research funders, and regulators is needed to address these devastating symptoms.

P- Reviewer: Durgam S, Maniglio R, Serafini G, Zhou X S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67-76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1299] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Saarni SI, Viertiö S, Perälä J, Koskinen S, Lönnqvist J, Suvisaari J. Quality of life of people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:386-394. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 160] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barnes TR, Leeson VC, Mutsatsa SH, Watt HC, Hutton SB, Joyce EM. Duration of untreated psychosis and social function: 1-year follow-up study of first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:203-209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Anthony WA, Blanch A. Supported employment for persons who are psychiatrically disabled: An historical and conceptual perspective. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1987;11:5-23. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 103] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, Taylor E. An economic evaluation of schizophrenia 1991. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:196-205. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Souetre E. Economic evaluation in schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 1997;35:67-69. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Trauer T, Duckmanton RA, Chiu E. Estimation of costs of public psychiatric treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:440-442. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:663-665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 213] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, Aggarwal J. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1122-1129. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Rössler W, Salize HJ, van Os J, Riecher-Rössler A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:399-409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 397] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Buchanan RW. Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1013-1022. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 305] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liemburg E, Castelein S, Stewart R, van der Gaag M, Aleman A, Knegtering H, Risk G. Two subdomains of negative symptoms in psychotic disorders: established and confirmed in two large cohorts. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:718-725. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 150] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Velligan DI, Maglinte GA, Sierra C, Martin ML. Corey-Lisle. Novel assessment tool for patients with schizophrenia: Development of the daily activity report. Presented at The International Society for CNS Clinical Trials and Methodology; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; September 30-October 2, 2013. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Messinger JW, Trémeau F, Antonius D, Mendelsohn E, Prudent V, Stanford AD, Malaspina D. Avolition and expressive deficits capture negative symptom phenomenology: implications for DSM-5 and schizophrenia research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:161-168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stahl SM, Buckley PF. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a problem that will not go away. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:4-11. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Boonstra N, Klaassen R, Sytema S, Marshall M, De Haan L, Wunderink L, Wiersma D. Duration of untreated psychosis and negative symptoms--a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Schizophr Res. 2012;142:12-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 157] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chang WC, Hui CL, Tang JY, Wong GH, Lam MM, Chan SK, Chen EY. Persistent negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia: a prospective three-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;133:22-28. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Garibaldi G, Bugarski-Kirola D, Berardo CG, Kapur S. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of CATIE data. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:147-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 244] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kurtz MM, Moberg PJ, Ragland JD, Gur RC, Gur RE. Symptoms versus neurocognitive test performance as predictors of psychosocial status in schizophrenia: a 1- and 4-year prospective study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:167-174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:495-506. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 638] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A, Correll CU, Cornblatt B. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:37-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Valmaggia LR, Stahl D, Yung AR, Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, McGuire PK. Negative psychotic symptoms and impaired role functioning predict transition outcomes in the at-risk mental state: a latent class cluster analysis study. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2311-2325. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hovington CL, Bodnar M, Joober R, Malla AK, Lepage M. Identifying persistent negative symptoms in first episode psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bambole V, Shah N, Sonavane S, Johnston M, Shrivastava A. Study of negatives symptoms in first episode schizophrenia. Open Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;3:323-328. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Makinen J, Miettunen J, Isohanni M, Koponen H. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia-a review. Nord J Psychiat. 2008;62:334-341. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Arango C, Buchanan R, Kirkpatrick B, Carpenter W. The deficit syndrome in schizophrenia: Implications for the treatment of negative symptoms. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:21-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Carpenter WT, Kirkpatrick B. The heterogeneity of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1988;14:645-652. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fenton WS, Wyatt RJ, McGlashan TH. Risk factors for spontaneous dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:643-650. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tiryaki A, Yazici MK, Anil AE, Kabakçi E, Karaağaoğlu E, Göğüş A. Reexamination of the characteristics of the deficit schizophrenia patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:221-227. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mayerhoff DI, Loebel AD, Alvir JM, Szymanski SR, Geisler SH, Borenstein M, Lieberman JA. The deficit state in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1417-1422. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bottlender R, Wegner U, Wittmann J, Strauss A, Möller HJ. Deficit syndromes in schizophrenic patients 15 years after their first hospitalisation: preliminary results of a follow-up study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249 Suppl 4:27-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kirkpatrick B, Amador XF, Flaum M, Yale SA, Gorman JM, Carpenter WT, Tohen M, McGlashan T. The deficit syndrome in the DSM-IV Field Trial: I. Alcohol and other drug abuse. Schizophr Res. 1996;20:69-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Buchanan RW, Gold JM. Negative symptoms: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11 Suppl 2:3-11. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Horan WP, Blanchard JJ. Neurocognitive, social, and emotional dysfunction in deficit syndrome schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;65:125-137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tek C, Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW. A five-year followup study of deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:253-260. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Buchanan RW, Strauss ME, Kirkpatrick B, Holstein C, Breier A, Carpenter WT. Neuropsychological impairments in deficit vs nondeficit forms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:804-811. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Buchanan R, Kirkpatrick B, Alphs LD, Chase TN, Carpenter WT. Limbic system abnormalities identified in schizophrenia using positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose and neocortical alterations with deficit syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:522-530. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 373] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Elkashef A, Munson RC, Gellad F, Carpenter WT. Structural abnormalities in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:59-65. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Grover S, Kulhara P. Deficit schizophrenia: Concept and validity. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:61-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:214-219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 882] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Alphs L. An industry perspective on the NIMH consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:225-230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Colibazzi T, Wexler BE, Bansal R, Hao X, Liu J, Sanchez-Peña J, Corcoran C, Lieberman JA, Peterson BS. Anatomical abnormalities in gray and white matter of the cortical surface in persons with schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55783. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Ananth H, Popescu I, Critchley HD, Good CD, Frackowiak RS, Dolan RJ. Cortical and subcortical gray matter abnormalities in schizophrenia determined through structural magnetic resonance imaging with optimized volumetric voxel-based morphometry. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1497-1505. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Eisenberger NI, Berkman ET, Inagaki TK, Rameson LT, Mashal NM, Irwin MR. Inflammation-induced anhedonia: endotoxin reduces ventral striatum responses to reward. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:748-754. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 395] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wüstenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, Wrase J, Heinz A. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2006;29:409-416. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Laviolette SR. Dopamine modulation of emotional processing in cortical and subcortical neural circuits: Evidence for a final common pathway in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:971-981. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Guillin O, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Neurobiology of dopamine in schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:1-39. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Dandash O, Fornito A, Lee J, Keefe RS, Chee MW, Adcock RA, Pantelis C, Wood SJ, Harrison BJ. Altered striatal functional connectivity in subjects with an at-risk mental state for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:904-913. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 131] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Andreasen NC, Ehrhardt JC, Swayze VW, Alliger RJ, Yuh WT, Cohen G, Ziebell S. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in schizophrenia. The pathophysiologic significance of structural abnormalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:35-44. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 274] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Breier A, Buchanan RW, Elkashef A, Munson RC, Kirkpatrick B, Gellad F. Brain morphology and schizophrenia. A magnetic resonance imaging study of limbic, prefrontal cortex, and caudate structures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:921-926. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 301] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Turetsky B, Cowell PE, Gur RC, Grossman RI, Shtasel DL, Gur RE. Frontal and temporal lobe brain volumes in schizophrenia. Relationship to symptoms and clinical subtype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1061-1070. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lim KO, Tew W, Kushner M, Chow K, Matsumoto B, DeLisi LE. Cortical gray matter volume deficit in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1548-1553. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Chua SE, Wright IC, Poline JB, Liddle PF, Murray RM, Frackowiak RS, Friston KJ, McGuire PK. Grey matter correlates of syndromes in schizophrenia: A semi-automated analysis of structural magnetic resonance images. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:406-410. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M. Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:585-594. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 373] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Flashman LA, Green MF. Review of cognition and brain structure in schizophrenia: profiles, longitudinal course, and effects of treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:1-18, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Roth RM, Flashman LA, Saykin AJ, McAllister TW, Vidaver R. Apathy in schizophrenia: reduced frontal lobe volume and neuropsychological deficits. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:157-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kim JJ, Crespo-Facorro B, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Magnotta V, Nopoulos P. Morphology of the lateral superior temporal gyrus in neuroleptic naïve patients with schizophrenia: relationship to symptoms. Schizophr Research. 2003;60:173-181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Millan MJ, Fone K, Steckler T, Horan WP. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical characteristics, pathophysiological substrates, experimental models and prospects for improved treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:645-692. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 223] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Beck AT, Rector NA, Stolar N, Grant PM. Schizophrenia: Cognitive theory, research, and therapy. New York: The Guilford Press 2009; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Velligan D, Maples N, Roberts DL, Medellin EM. Integrated Psychosocial Treatment for Negative Symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2014;17:1-19. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Granholm E, Ben-Zeev D, Link PC. Social disinterest attitudes and group cognitive-behavioral social skills training for functional disability in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:874-883. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 62. | Grant PM, Beck AT. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:798-806. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 246] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:253-260. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 557] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bustillo J, Lauriello J, Horan W, Keith S. The psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:163-175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Weisman AG, Nuechterlein KH, Goldstein MJ, Snyder KS. Controllability perceptions and reactions to symptoms of schizophrenia: a within-family comparison of relatives with high and low expressed emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:167-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Alphs L, Hill C, Cazorla P. Psychometric evaluation of the four-item Negative Symptom Assessment (NSA-4) in schizophrenic patients with predominant negative symptoms. New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, 47th Annual Meeting; Boca Raton, FL, 2007. . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Forbes C, Blanchard JJ, Bennett M, Horan WP, Kring A, Gur R. Initial development and preliminary validation of a new negative symptom measure: the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS). Schizophr Res. 2010;124:36-42. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13937] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14545] [Article Influence: 393.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, Fischer BA, Daniel DG, Cienfuegos A, Marder SR. The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:300-305. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 547] [Article Influence: 42.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: The University of Iowa 1984; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 71. | Velligan DI, Roberts D, Mintz J, Maples N, Li X, Medellin E, Brown M. A randomized pilot study of MOtiVation and Enhancement (MOVE) Training for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;165:175-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Velligan DI, Lopez L, Castillo DA, Manaugh B, Milam AC, Miller AL. Interrater reliability of using brief standardized outcome measures in a community mental health setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:558-560. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Buckley PF, Stahl SM. Pharmacologic treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia: therapeutic opportunity or Cul-de-sac? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:93-100. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Yassini M, Shariat N, Nadi M, Amini F, Vafaee M. The effects of bupropion on negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:1227-1233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Rummel C, Kissling W, Leucht S. Antidepressants for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD005581. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Velligan DI, Alphs LD. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: the importance of identification and treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2008;25:12. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Boyer P, Lecrubier Y, Puech AJ, Dewailly J, Aubin F. Treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia with amisulpride. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:68-72. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Loo H, Poirier-Littre MF, Theron M, Rein W, Fleurot O. Amisulpride versus placebo in the medium-term treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:18-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Danion JM, Rein W, Fleurot O. Improvement of schizophrenic patients with primary negative symptoms treated with amisulpride. Amisulpride Study Group. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:610-616. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 80. | Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:94-103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 345] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Umbricht D, Alberati D, Martin-Facklam M, Borroni E, Youssef EA, Ostland M, Wallace TL, Knoflach F, Dorflinger E, Wettstein JG. Effect of bitopertin, a glycine reuptake inhibitor, on negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, proof-of-concept study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:637-646. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 164] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Kingwell K. Schizophrenia drug gets negative results for negative symptoms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:244-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Coyle JT, Basu A, Benneyworth M, Balu D, Konopaske G. Glutamatergic synaptic dysregulation in schizophrenia: therapeutic implications. Novel Antischizophrenia Treatments. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer 2012; 267-295. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 84. | Roffman JL, Lamberti JS, Achtyes E, Macklin EA, Galendez GC, Raeke LH, Silverstein NJ, Smoller JW, Hill M, Goff DC. Randomized multicenter investigation of folate plus vitamin B12 supplementation in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:481-489. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 85. | Arango C, Garibaldi G, Marder SR. Pharmacological approaches to treating negative symptoms: a review of clinical trials. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:346-352. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Kern RS, Glynn SM, Horan WP, Marder SR. Psychosocial treatments to promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:347-361. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Patterson TL, Leeuwenkamp OR. Adjunctive psychosocial therapies for the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:108-119. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Grant PM, Reisweber J, Luther L, Brinen AP, Beck AT. Successfully breaking a 20-year cycle of hospitalizations with recovery-oriented cognitive therapy for schizophrenia. Psychol Serv. 2014;11:125-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Valmaggia LR, van der Gaag M, Tarrier N, Pijnenborg M, Slooff CJ. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for refractory psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia resistant to atypical antipsychotic medication. Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:324-330. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Röhricht F, Priebe S. Effect of body-oriented psychological therapy on negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2006;36:669-678. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, Kechavan M, Cooley S, DiBarry AL, Garrett A. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:866-876. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 311] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1468-1476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Demily C, Franck N. Cognitive remediation: a promising tool for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:1029-1036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Bellack AS. Skills training for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:375-391. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:21-46. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 96. | Draper ML, Stutes DS, Maples NJ, Velligan DI. Cognitive adaptation training for outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:842-853. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Velligan DI, Diamond PM, Mintz J, Maples N, Li X, Zeber J, Ereshefsky L, Lam YW, Castillo D, Miller AL. The use of individually tailored environmental supports to improve medication adherence and outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:483-493. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger C, Ritch J, Ledbetter N, Prihoda TJ, Miller AL. Randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies to enhance adaptive functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1317-1323. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 99. | Velligan DI, Diamond PM, Maples NJ, Mintz J, Li X, Glahn DC, Miller AL. Comparing the efficacy of interventions that use environmental supports to improve outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:312-319. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Lessof MH, Youlten LJ, Heavey D, Kemeny DM, Dollery C. Local mediator release in bee venom anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:231-232. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Velligan DI, Alphs L, Lancaster S, Morlock R, Mintz J. Association between changes on the Negative Symptom Assessment scale (NSA-16) and measures of functional outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169:97-100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Roberts DL, Penn DL. Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for outpatients with schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;166:141-147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 218] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Liberman RP, Glynn S, Blair KE, Ross D, Marder SR. In vivo amplified skills training: promoting generalization of independent living skills for clients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2002;65:137-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |