Lyme disease: summary of NICE guidance

BMJ 2018; 361 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1261 (Published 12 April 2018) Cite this as: BMJ 2018;361:k1261

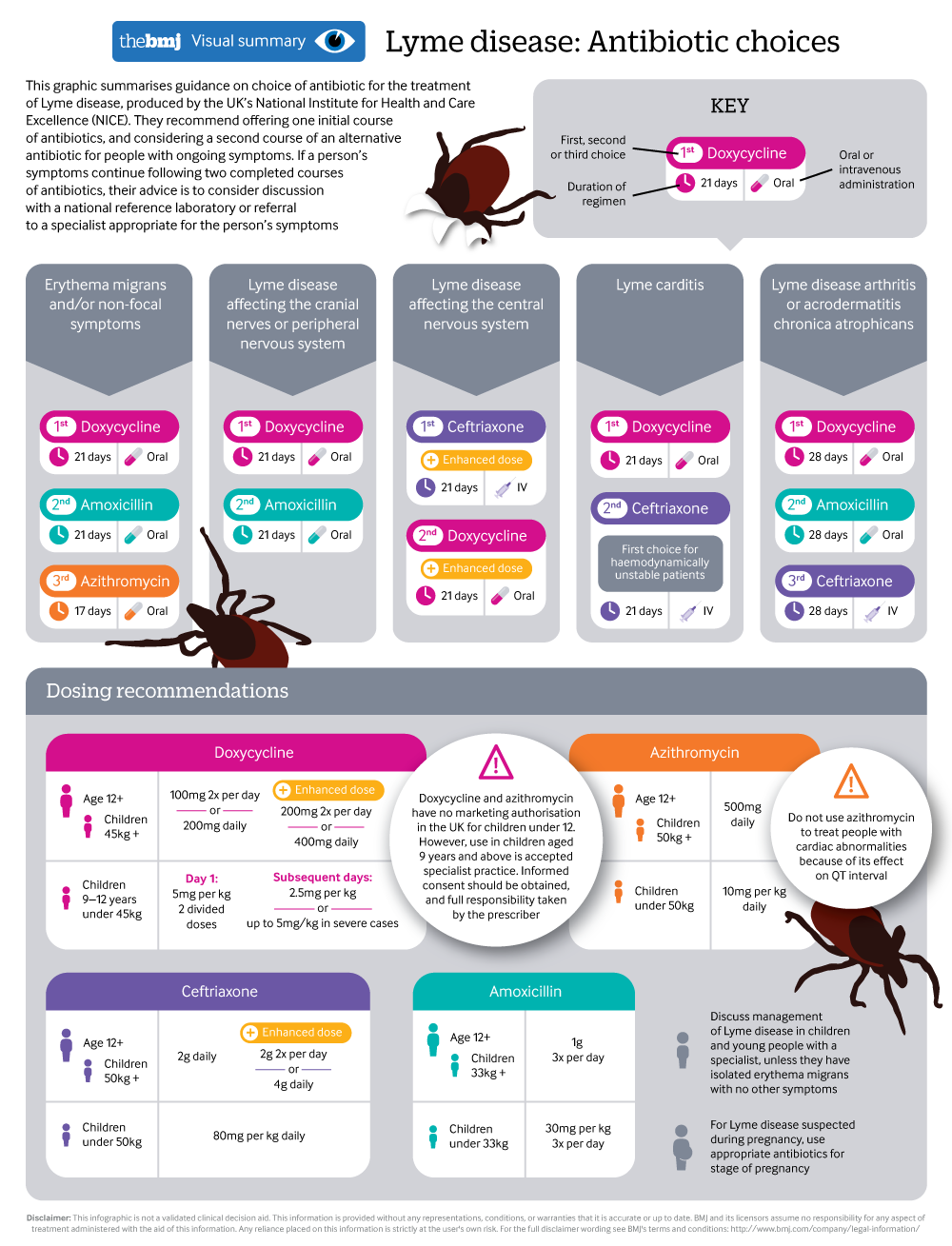

Antibiotic choices when treating Lyme disease

A visual summary summarises latest NICE guidance

- Maria Cruickshank, senior research fellow1,

- Norma O’Flynn, chief operating officer1,

- Saul N Faust, professor of paediatric immunology and infectious diseases, director of NIHR Clinical Research Facility2

- on behalf of the Guideline Committee

- 1National Guideline Centre, Royal College of Physicians, London

- 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, and University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, UK

- Correspondence to: S N Faust s.faust{at}soton.ac.uk

What you need to know

Lyme disease can occur anywhere in the UK

Erythema migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease. Use a combination of clinical presentation and laboratory testing to guide diagnosis and treatment in people without erythema migrans

Serological testing is a two tier approach: a sensitive initial test is performed first (ELISA), followed by a more specific confirmatory test (immunoblot) in case of a positive or equivocal initial result

Symptoms of Lyme disease may take months or years to resolve even after treatment for several reasons, including alternative diagnoses, reinfection, treatment failure, immune reaction, and organ damage caused by Lyme disease

Consider a second course of antibiotics for people with ongoing symptoms as treatment may have failed

Lyme disease is caused by a specific group of Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, which can be transmitted to humans through a bite from an infected tick. This can result in a number of clinical problems ranging from skin rash to serious involvement of organ systems, including arthritis, and neurological problems. People with skin and non-specific symptoms most commonly present to their general practitioner and are often treated in primary care, whereas people with symptoms affecting organ systems are commonly referred to specialists.

The guideline focuses on diagnosis and management of Lyme disease according to clinical presentation and symptoms rather than using the differing classifications of Lyme disease, which are poorly defined and contested. There is a lack of good quality evidence on the epidemiology, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of Lyme disease.

This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).1

What’s new in this guidance

Tests used to support diagnosis should be carried out at UK accreditation service (UKAS) accredited laboratories that use validated tests and participate in a formal external quality assurance programme

Doses and durations of antibiotics at the higher ranges of formulary doses and lengths of treatment are recommended

Consider a second course of antibiotics for people with ongoing symptoms if treatment may have failed

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations are based on the Guideline Committee’s experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice. Evidence levels for the recommendations are given in italic in square brackets.

Awareness

The incidence of Lyme disease is unknown. Most estimates are based on laboratory confirmed cases and therefore do not include those diagnosed on clinical presentation alone or those that go undiagnosed. The indicative rash, erythema migrans, is not always present, noticed, or recognised, and other symptoms overlap with many other common conditions. The following recommendations were developed to raise awareness of factors affecting Lyme disease risk and when to suspect Lyme disease.

Be aware that:

The bacteria that cause Lyme disease are transmitted by the bite of an infected tick

Ticks are mainly found in grassy and wooded areas, including urban gardens and parks

Tick bites may not always be noticed

Infected ticks are found throughout the UK and Ireland; although some areas seem to have a higher prevalence of infected ticks, prevalence data are incomplete

Particularly high risk areas are the south of England and Scottish Highlands, but infection can occur in many areas

Lyme disease may be more prevalent in parts of central, eastern, and northern Europe (including Scandinavia) and parts of Asia, the US, and Canada.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the Guideline Committee (GC) and informed by an evidence review on Lyme disease incidence in the UK]

Be aware that most tick bites do not transmit Lyme disease. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Give people advice about:

Where ticks are commonly found (such as grassy and wooded areas, including urban gardens and parks)

The importance of prompt, correct tick removal and how to do this (see box 1)

Covering exposed skin and using insect repellents that protect against ticks

How to check themselves and their children for ticks on the skin

Sources of information on Lyme disease, such as Public Health England, and organisations providing information and support, such as patient charities.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Correct removal of ticks*

If you have been bitten, remove the tick as soon as possible

The safest way to remove a tick is to use a pair of fine-tipped tweezers or a tick removal tool

Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible

Pull upwards slowly and firmly, as tick mouthparts left in the skin can cause a local infection

Once the tick is removed, apply antiseptic to the bite area or wash with soap and water and keep an eye on it for several weeks for any changes

Contact your general practice if you start to feel unwell and remember to tell the staff you were bitten by a tick or have recently spent time outdoors

*Advice from Public Health England. Ticks and your health: Information about tick bite risks and prevention. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/552740/Ticksandyourhealthinfoabouttickbites.pdf

Diagnosis

Figure 1 details the guidance for use of tests in diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Algorithm for laboratory investigations and diagnosis of Lyme disease

Diagnose Lyme disease in people with erythema migrans (fig 2), a red rash that:

Increases in size and may sometimes have a central clearing

Is not usually itchy, hot, or painful

Usually becomes visible from one to four weeks (but can appear from 3 days to 3 months) after a tick bite and lasts for several weeks

Is usually at the site of a tick bite.

Be aware that a rash that is not erythema migrans can develop as a reaction to a tick bite. This rash:

Usually develops and recedes within 48 hours from the time of the tick bite

Is more likely than erythema migrans to be hot, itchy or painful

May be caused by an inflammatory reaction or infection with a common skin pathogen.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Consider the possibility of Lyme disease in people presenting with several of the following symptoms, because Lyme disease is a possible but uncommon cause of:

Fever and sweats

Swollen glands

Malaise

Fatigue

Neck pain or stiffness

Migratory joint or muscle aches and pain

Cognitive impairment such as memory problems and difficulty concentrating (sometimes described as “brain fog”)

Headache

Paraesthesia.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Consider the possibility of Lyme disease in people presenting with symptoms and signs relating to one or more organ systems (focal symptoms) because Lyme disease is a possible but uncommon cause of:

Neurological symptoms (such as facial palsy or other unexplained cranial nerve palsies, meningitis, mononeuritis multiplex or other unexplained radiculopathy, or, rarely, encephalitis, neuropsychiatric presentations, or unexplained white matter changes on brain imaging)

Inflammatory arthritis affecting one or more joints that may be fluctuating and migratory

Cardiac problems such as heart block or pericarditis

Eye symptoms such as uveitis or keratitis

Skin rashes such as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans or lymphocytoma.

[Based on very low quality evidence from observational studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

If a person presents with symptoms that suggest the possibility of Lyme disease, explore how long the person has had symptoms and their history of possible tick exposure.

For example, ask about:

Activities that might have exposed them to ticks

Travel to areas where Lyme disease is known to be highly prevalent.

Do not rule out the possibility of Lyme disease in people with symptoms but no clear history of tick exposure.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Use a combination of clinical presentation and laboratory testing to guide diagnosis and treatment in people without erythema migrans (see fig 1). Do not rule out diagnosis if tests are negative but there is high clinical suspicion of Lyme disease. [Based on very low quality evidence from observational studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

The most common laboratory tests used when Lyme disease is suspected are serological tests that detect antibodies to the bacteria causing Lyme disease. This is based on a two tier approach, where a sensitive initial test is performed first, followed by a more specific confirmatory test in case of a positive or equivocal initial test result. When combined with clinical assessment, the tests can be helpful in supporting diagnosis.

Carry out tests for Lyme disease only at UK accreditation service (UKAS) accredited laboratories that:

Use validated tests (validation should include published evidence on the test methodology, its relation to Lyme disease, and independent reports of performance)

Participate in a formal external quality assurance programme.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Management

The recommendations on antibiotic management aim to provide clear guidance on choice of antibiotic, dose, treatment duration, and circumstances when additional courses of treatment or referral to specialists might be considered. Doses and duration of antibiotic treatment have been chosen at the higher ranges of formulary doses and lengths of treatment to avoid the possibility of under-treatment. There was a lack of evidence to support extended courses of antibiotics for people with persisting symptoms.

Treat people with Lyme disease according to the infographic (also supplementary tables 1 and 2 on bmj.com)

Discuss diagnosis and management of all children and young people with Lyme disease and symptoms in addition to erythema migrans with a specialist

If an adult with Lyme disease has focal symptoms, consider a discussion with or referral to an appropriate specialist without delaying treatment

If symptoms that may be related to Lyme disease persist, do not continue to improve, or worsen after antibiotic treatment, review the person's history and symptoms to explore:

Possible alternative causes of the symptoms

If reinfection may have occurred

If treatment may have failed

Details of previous treatment, including whether the course of antibiotics was completed without interruption

If symptoms may be related to organ damage caused by Lyme disease, such as nerve palsy.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Consider a second course of antibiotics for people with ongoing symptoms if treatment may have failed. Use an alternative antibiotic to the initial course. For example, for adults with Lyme disease and arthritis, offer amoxicillin if the person has completed an initial course of doxycycline. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

If a person has ongoing symptoms after two completed courses of antibiotics for Lyme disease:

Do not routinely offer further antibiotics and

Consider discussion with the English or Scottish national reference laboratory or discussion or referral to a specialist appropriate for the person’s symptoms (such as an adult or paediatric infection specialist, rheumatologist, or neurologist).

[Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Support people who have ongoing symptoms after treatment for Lyme disease by:

Encouraging and helping them to access additional services, including referring them to adult social care for a care and support needs assessment if they would benefit from these

Communicating with children and families social care, schools and higher education, and employers about the person’s need for a gradual return to activities, if relevant.

Explain the diagnosis and uncertainties

The uncertainty that exists as a result of lack of good evidence is difficult for people with Lyme disease and can lead to fear and frustration. It is essential that people with diagnosed or suspected Lyme disease are provided with support as well as direction to good sources of information and clear communication about diagnosis and management, including uncertainties.

Tell people that tests for Lyme disease have limitations. Explain that both false positive and false negative results can occur and what this means. [Based on very low quality evidence from observational studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Explain that most tests for Lyme disease assess the presence of antibodies and that the accuracy of tests may be reduced if:

Testing is carried out too early (before antibodies have developed)

The person has reduced immunity (such as a person receiving immunosuppressant treatment) which might affect the development of antibodies.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Explain to people with ongoing symptoms after antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease that:

Continuing symptoms may not mean they still have an active infection

Symptoms of Lyme disease may take months or years to resolve even after treatment

Some symptoms may be a consequence of permanent damage from infection

There is no test for active infection and an alternative diagnosis may explain their symptoms.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Implementation

NICE has produced tools and resources to facilitate the implementation of this guideline, including an algorithm for laboratory investigations and diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Guidelines into practice

Which groups of patients do you tend to test or treat for Lyme's disease? Does this guideline provide ideas on how to alter your practice?

Which groups of patients would you discuss with a specialist for suspected Lyme's disease? Does this guideline provide ideas on how to alter your practice?

How might you share learning from this guideline with colleagues?

Further information on the guidance

Methods

This guidance was developed by the National Guideline Centre in accordance with NICE guideline development methods (www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual.pdf).

The Guideline Committee (GC) established by the National Guideline Centre comprised one professor of paediatric immunology and infectious diseases, two paediatric consultants in infectious diseases, one consultant in infectious diseases, one general physician, one microbiologist, one paediatric neurologist, one rheumatologist, two general practitioners, and four lay members. The GC also co-opted an adult neurologist and a pharmacist.

Review questions were developed based on key clinical areas of the scope. Systematic literature searches, critical appraisals, evidence reviews, and evaluations of cost effectiveness, where appropriate, were completed for all questions except for awareness of Lyme disease. The recommendations for raising awareness were based on discussions, consensus, and expert opinion of the GC and were also informed by other review questions. A qualitative review was undertaken to explore aspects related to the information needs of people with suspected, confirmed, or treated Lyme disease.

Quality ratings of the evidence were based on GRADE methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). These relate to the quality of the available evidence for assessed outcomes or themes rather than the quality of the study.

The scope and the draft of the guideline went through a rigorous reviewing process, in which stakeholder organisations were invited to comment; the GC took all comments into consideration when producing the final version of the guideline.

A formal review of the need to update a guideline is usually undertaken by NICE after its publication. NICE will conduct a review to determine whether the evidence base has progressed significantly to alter the guideline recommendations and warrants an update.

Other details

Different versions of this guideline have been produced: a short version containing a list of all the recommendations and a summary of why they were developed, known as the “short guideline,” and individual evidence reports containing all the evidence, the process undertaken to develop the recommendations, and all the recommendations. These are available from the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG95).

Future research

The GC prioritised the following research recommendations:

Can a core outcome set be developed for clinical trials of management of Lyme disease?

What are the incidence, presenting features, management and outcome of Lyme disease in the UK?

What is the current seroprevalence of Lyme disease-specific antibodies and other tick-borne infections in people in the UK?

What are the most clinically and cost effective treatment options for different clinical presentations of Lyme disease in the UK?

What is the most clinically and cost effective serological antibody-based test, biomarker, or other test for diagnosing Lyme disease in the UK at all stages, including reinfection?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

Committee members involved in this guideline update included four lay members who contributed to the formulation of the recommendations summarised here.

Footnotes

The members of the Guideline Committee: Srini Bandi, Stephen Barton, Nick Beeching, Robin Brittain-Long, Tim Brooks, Nick Davies, Saul Faust, Scott Hackett, Cheryl Hemingway, Neil Hopkinson, Rebecca Houghton, Veronica Hughes, Stella Huyshe-Shires, Melissa McCullough, Caroline Rayment, David Stephens.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the initial draft of this article, helped revise the manuscript, approved the final draft for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the article.

Funding: The National Guideline Centre was commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to develop this guideline and write this BMJ summary.

Competing interests: We declare the following interests based on NICE’s policy on conflicts of interests (available at www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/Who-we-are/Policies-and-procedures/code-of-practice-for-declaring-and-managing-conflicts-of-interest.pdf). MC and NO’F have no relevant interests to declare. SNF provides a full statement in the NICE guideline (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG95).

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.